CRYPTOGRAPHY

The elementary form of a communication system is two parties, often referred to as Alice and Bob, who would like to exchange some information. In the presence of channel noise, the transmitted and received information will exhibit some inconsistency which can be mitigated through the use of an error correcting code (ECC). In addition to the intended message, redundant data is included to ensure error-free communication. The needed number of error-correcting bits is directly proportional to the channel noise, which was first mathematically quantified by Claude Shannon in 1948 [1].

Communication links are prone to eavesdropping, where an adversary, often named Eve, gains access to the exchanged message. The countermeasure is to conceal the raw message, known as plaintext, by encryption. The encrypted message, referred to as ciphertext, can be mapped back to the original message only by the intended recipient possessing the necessary knowledge.

Symmetric key cryptography is the case where the same key is used to encrypt and decrypt the message. The secrecy of the message may stem from the undisclosed key and the obscurity of the used cipher. The latter is known as security through obscurity, which is discouraged as design leakage will render all the developed hardware obsolete [2], similar to what happened to the Enigma machine utilized by the Germans in WWII. Therefore, the conventional practice is to utilize an unrevealed key with a reliable encryption algorithm. Some algorithms, like the substitution cipher (e.g., Caeser), are prone to elemental attacks (e.g., frequency analysis), rendering them not secure for symmetric key encryption. Once again, Claude Shannon was the one to set the foundation of modern cryptography in his 1949 work [3], where he introduced the framework upon which ciphers are evaluated. Aside from the one-time pad (OTP), all ciphers are breakable for some available computational power. What distinguishes one cipher from another is the amount of time needed to crack it. For example, the advanced encryption standard (AES), developed in 1999 [4] and the most commonly used symmetric algorithm, requires billions of years to brute-force with the strongest existing supercomputer. In the OTP cipher, the bitwise exclusive or (XOR) operation is utilized to encrypt the message with a same-size key. As its name suggests, the OTP cipher uses the key only once, making it impractical since the pre-shared key will be quickly exhausted.

When the keys used for encryption and decryption are different, the process is called asymmetric (public-key) cryptography, elevating the burden of key sharing in symmetric cryptography. The encryption (public) key is disclosed, while the decryption (private) key is kept secret. Inspired by Ralph Merkle’s work [5], the distribution of keys over a public channel was first made possible by the Diffie-Hellman algorithm in 1976 [6]. One of the oldest and most widely used public-key cryptosystems is the Rivest-Shamir-Adleman (RSA) algorithm [7]. In practice, rather than message transmission, RSA is used to distribute the keys for the less computationally demanding symmetric key cryptography, enabling high throughput secure data transmission. The security of RSA stems from the practical difficulty of factoring large prime numbers, which is threatened by the anticipated advent of quantum computers capable of running Shor’s prime factorization algorithm [8].

In order to hinder the attacks posed by quantum computers, a new family of quantum-resistant ciphers has been developed lately in what is known as post-quantum cryptography (PQC). Another countermeasure is to share the keys using quantum key distribution (QKD), a physical layer approach that relies on quantum mechanical phenomena to establish symmetric keys between two authenticated parties. Unlike PQC, QKD is future-proof, in the sense that its security remains with the advancements in hardware and software algorithms [9].

QUANTUM KEY DISTRIBUTION (QKD)

QKD relies on the fact that quantum states cannot be observed without altering them, a concept that came to be known as the no-cloning theorem [10]. The no-cloning theorem, which originated from James Parks’ work in 1970 [11], dictates that quantum states are always disturbed when measured and thus cannot be copied. By quantifying the amount of disturbance and its origins, secure quantum states can be exchanged, from which a cryptographic key is extracted. The stages of any QKD protocol are listed below.

- Quantum Communication: Preparation, distribution, and measurement of quantum states.

- Parameter Estimation: A small subset of Alice’s and Bob’s data is publicly disclosed to determine the amount of information that could have leaked to Eve. The communication is aborted if the leaked information is above a certain threshold.

- Sifting: Public announcements regarding the data by Alice and Bob, which allows them to obtain an equal size key with a small bit error rate (BER).

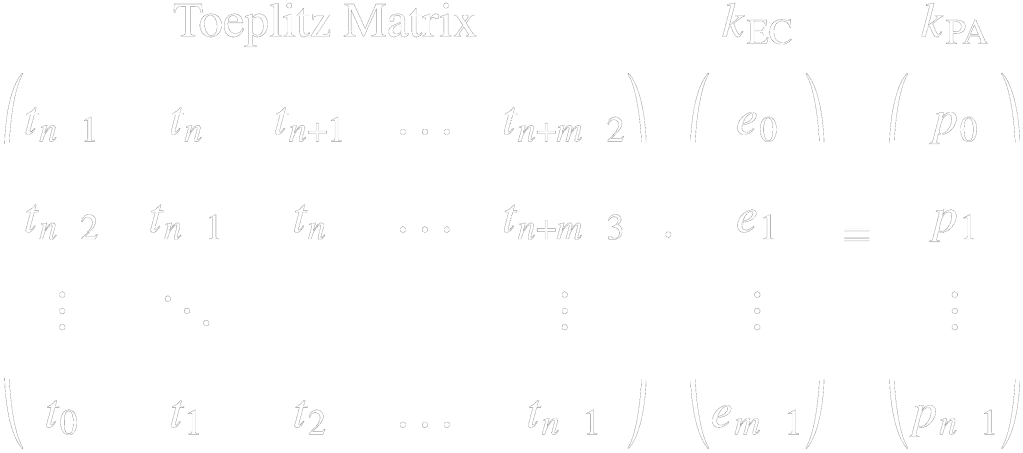

- Error-Correction: The key obtained from the sifting stage is transformed into an identical pair of keys (kEC) with a smaller size 𝑚 using error-correction techniques.

- Privacy Amplification: In order to eliminate the information leaked to Eve, privacy amplification is performed, which further reduces the size of the key to 𝑛 bits but guarantees the security of the obtained key (kPA) up to a factor 𝜖. This can be done through a matrix-vector multiplication operation where the vector is the error-corrected key (kEC) and the matrix is a Toeplitz (diagonal-constant) [12].

The first conceived QKD protocol is the BB84 discrete-variable quantum key distribution (DV-QKD), named after its inventors Brassard and Bennett, which encodes the quantum states in the polarization of light [13]. Regarding how the signal is received, QKD can be classified into two categories: continuous-variable quantum key distribution (CV-QKD) and DV-QKD. As portrayed in Figure 1.2, the latter utilizes the discrete particle nature of light to encode the state, which is received using a single-photon detector (SPD). DV-QKD is currently more mature than CV-QKD, as it is easier to analyze using standard mathematical tools and is more heavily investigated [14]. However, the infinite-dimensional phase space of CV-QKD requires complex mathematical tools, such as symplectic transformations, making it harder to analyze compared to DV-QKD [15]. Moreover, CV-QKD requires sophisticated digital signal processing (DSP) algorithms [16].

Despite this, the practical implementation of CV-QKD systems is much more feasible. Unlike DV-QKD, which requires bulky, expensive, and dead time-limited single-photon detectors, CV-QKD utilizes compact and relatively inexpensive coherent receivers that operate at a higher data rate. Moreover, the existing optical telecommunication infrastructure already uses coherent receivers, making deploying CV-QKD systems easier [17]. Thus, while DV-QKD is currently more well-established, the practical advantages of CV-QKD suggest that it may become an increasingly important technique for QKD.

| QKD Class | Receiver Type | Availability | Operating Temp. | Cost | Size |

| Discrete-Variable (DV) | Photon Counting | Custom-Built | Requires Cooling | Expensive | Bulky |

| Continuous-Variable (CV) | Homodyne Detection | Commercial | Room-Temperature | Cheap | Small |

instead of a single photon detector (SPD) for discrete-variable (DV) QKD

implementation.

Relevant Work

- A. Alsaui et al., “Machine learning and time-series decomposition for phase extraction and symbol classification in CV-QKD”, Phys. Scr., vol. 99, no. 7, p. 076 008, 2024

- A. Alsaui et al., “Digital filter design for experimental continuous-variable quantum key distribution”, in Proc. Opt. Fiber Commun. Conf. Exhib. (OFC), San Diego, CA, USA, 2023, pp. 1–3.

- Y. Alwehaibi et al., “Experimental characterization of a simple entanglement distribution link”, in Optica Quantum 2.0 Conference and Exhibition, Optica Publishing Group, 2023, QTu3A.40.

- Alsaui, Abdulmohsen. Coherent Optical Communication Techniques for Experimental Continuous-Variable Quantum Key Distribution. Diss. Indian Institute of Technology Madras, 2023.

References

- C. E. Shannon, “A mathematical theory of communication,” The Bell system technical journal, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 379–423, 1948.

- K. Scarfone, W. Jansen, M. Tracy, et al., “Guide to general server security,” NIST Special Publication, vol. 800, no. 123, 2008.

- C. E. Shannon, “Communication theory of secrecy systems,” The Bell system technical journal, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 656–715, 1949.

- J. Daemen and V. Rijmen, “Aes proposal: Rijndael,” 1999.

- R. C. Merkle, “Secure communications over insecure channels,” Communications of the ACM, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 294–299, 1978.

- W. Diffie, “New direction in cryptography,” IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory, vol. 22, pp. 472–492, 1976.

- R. L. Rivest, A. Shamir, and L. Adleman, “A method for obtaining digital signatures and public-key cryptosystems,” Communications of the ACM, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 120–126, 1978.

- P. W. Shor, “Algorithms for quantum computation: Discrete logarithms and factoring,” in Proceedings 35th annual symposium on foundations of computer science, Ieee, 1994, pp. 124–134.

- R. Renner and R. Wolf, “Quantum advantage in cryptography,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.04078, 2022.

- W. K. Wootters and W. H. Zurek, “A single quantum cannot be cloned,” Nature, vol. 299, no. 5886, pp. 802–803, 1982.

- J. L. Park, “The concept of transition in quantum mechanics,” Foundations of physics, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 23–33, 1970.

- B.-Y. Tang, B. Liu, Y.-P. Zhai, C.-Q. Wu, and W.-R. Yu, “High-speed and large-scale privacy amplification scheme for quantum key distribution,” Scientific reports, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–8, 2019.